5 things you may not know about Luxembourg American Cemetery

Luxembourg American Cemetery is located in Hamm, Luxembourg. This World War II American Battle Monuments Commission site contains the graves of approximately 5,100 service members. Approximately 400 names are commemorated on its walls of the missing. It is also the final resting place of Gen. George S. Patton.

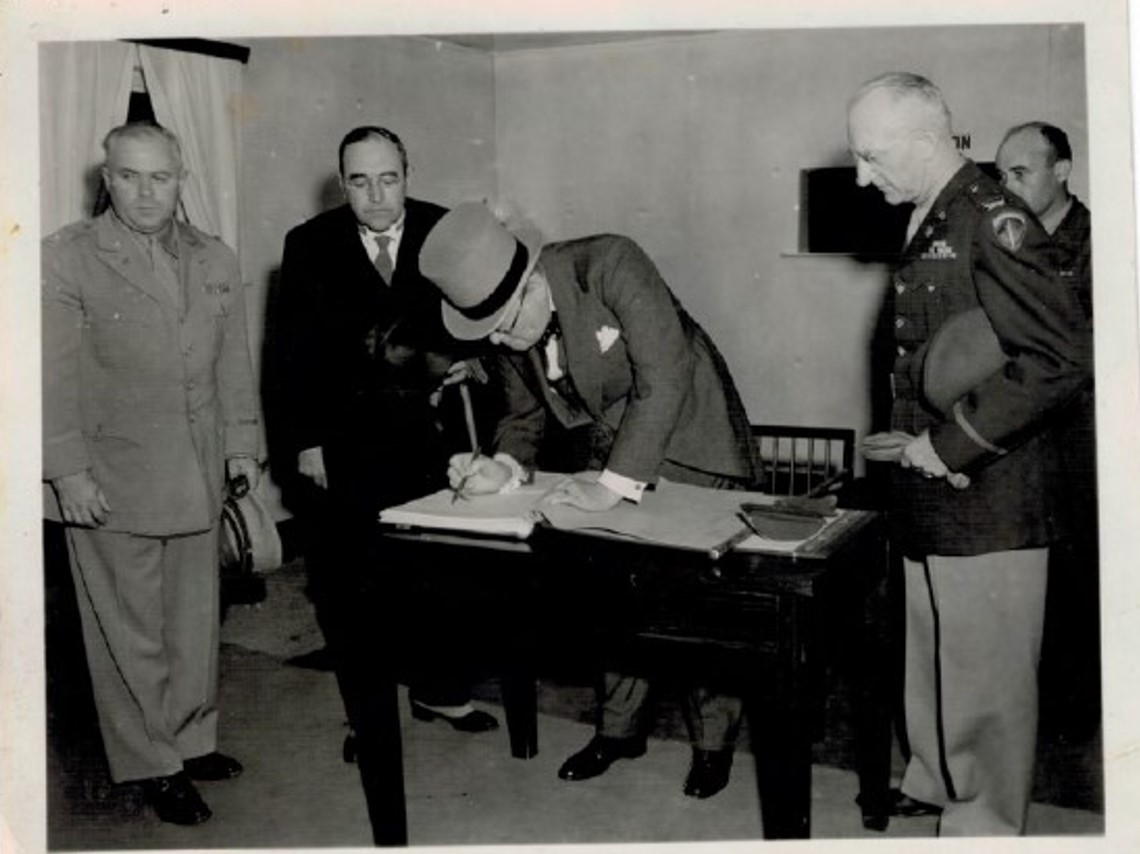

UK Prime Minister Winston Churchill visited the site

Winston Churchill visited Luxembourg in July 1946, while he was not the U.K. prime minister anymore. This visit was extensively covered in the press at the time, using headlines like “Good Old Winston Churchill” in the Obermosel Zeitung or “Luxembourg’s big day” in the Escher Tageblatt.

On July 15, 1946, Churchill went to Luxembourg American Cemetery with his son and daughter where he paid his respects to the U.S. service members buried and memorialized, and placed a wreath at Patton’s grave. He also signed the guest register before leaving the cemetery.

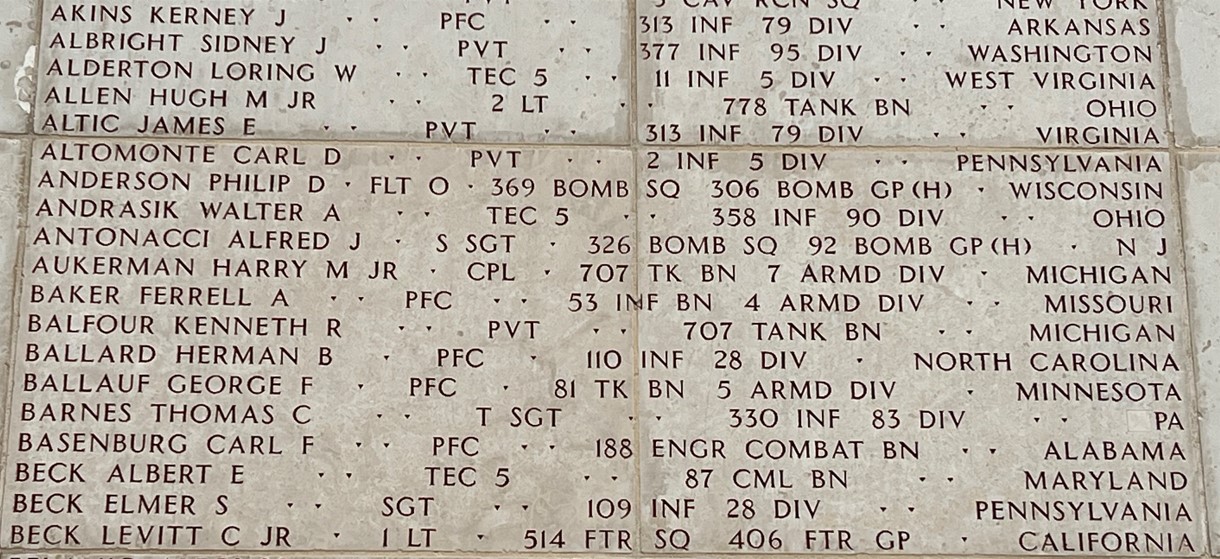

U.S. service member who died in Buchenwald listed on Wall of the Missing

On June 29, 1944, 1st. Lt. Levitt C. Beck, a member of the 514th Fighter Squadron, 406th Fighter Group, was hit by German fire during a bombing mission southwest of Paris. He landed near Dreux, France, where he was helped by a young French man and given civilian clothing. He found refuge in the town of Anet, France. That is where he started writing his story, sheltered by the French Resistance who asked him to stay hidden until the liberation. However, he wanted to break out and go back to England to rejoin his unit. He left his manuscript there, which was to be sent to his parents if he did not come back.

He never made it back to England as a few days after his departure, the night of July 17-18, he was betrayed and brought to the headquarters of Gestapo Avenue Foch in Paris. On Aug. 15, 1944, the Gestapo forced a group of 168 Allied airmen into cattle cars in Pantin, France. Beck was one of them. Their destination was the SS-run concentration camp of Buchenwald.

In October 1944, he contracted pneumonia after being compelled to stand out in the rain and sleep in his wet clothes. He died in Buchenwald infirmary the night of Oct. 29-30, 1944, but German officials gave Oct. 31 as his date of death. He was cremated by the SS and became one of Buchenwald’s victims. Most of the other flyers were transferred to Stalag Luft III after being discovered by a group of Luftwaffe officials.

Beck’s manuscript was sent to his parents in Huntington Park in early January 1946 and published as a book under the title “Fighter Pilot.”

Beck is remembered on the Wall of the Missing at Luxembourg American Cemetery.

The “Mad Russian” buried at Luxembourg American Cemetery

Alexis Sommaripa known as the “Mad Russian” in World War II was born in Odessa, Russia in 1900. He immigrated to the U.S. in 1918 after graduating from the Imperial Law School. In the U.S., he obtained a master’s degree from Harvard.

In December 1941, he enlisted even though he was 41 years old at the time. He was convinced that with his language skills he could be an asset for the military and a perfect spy, but it did not happen. He was sent to Camp Lee, Virginia, where he trained. Then, he was sent to England as an Office of Strategic Services civilian technician, with an assimilated rank of captain, where he reported to Col. David K. E. Bruce, head of OSS operations in the European Theater of Operations.

On June 9, 1944, Sommaripa landed on Omaha Beach in Normandy, France, where he started gathering intelligence. He took part in combat in Carentan and Mortain where he got the idea of using his language skills to talk the enemy into surrendering. He was assigned to the Second Mobile Radio Company, responsible for the propaganda of the U.S. armyforces in Europe. They accompanied the First and Third armies in Operation Overlord, where they were responsible for disseminating leaflets fired in 105mm shells to encourage the Germans to give up. They were also responsible for battlefield broadcasts from loudspeaker-rigged half-ton trucks, for keeping French civilians in the loop during operations, for setting up broadcasting stations in conquered cities and towns; and with monitoring enemy propaganda broadcasts. Sommaripa was given minimal instructions, but he eventually established an unbelievable record in terms of enemy soldiers he convinced to surrender. The result exceeded all expectations. He was later attached to the 37th Tank Battalion, 4th Armored Division, Third Army.

Sommaripa continued serving with the 4th Armored Division as it went across France and reached the German border. During the Battle of the Bulge, his division broke through to the encircled garrison at Bastogne and helped to put the Germans in full retreat to Germany. It was shortly after crossing the Rhine, that Sommaripa’s fate changed.

On March 28, 1945, during an attack on Göbelnrod, two companies of the 35th Tank Battalion and one company of the 51st Armored Infantry Battalion were bogged down about 1,200 yards from the village. As Sommaripa slowly crawled toward the main thoroughfare, constantly under enemy observation, he kept up a constant chatter over his two loudspeakers, instructing the German defenders to cease firing and surrender, which enabled the American infantry to easily walk in and take over the town. Four hours later, 15 miles from there, while maneuvering to target another group of German soldiers, Sommaripa’s M5A1 tank was strafed by a fighter aircraft (possibly American). The tank’s driver was wounded, and as he fell, his feet hit the controls, causing the tank to veer wildly and overturn into a bomb crater, throwing Sommaripa out of the vehicle. The tank then landed on top of him, killing him. Sommaripa received several awards including the Purple Heart.

Twenty years after his father’s death, his son received his diary mentioning his nickname, “Mad Russian,” affectionately given by Lt. Col. Creighton W. Abrams, commander of the 37th Tank Battalion, 4th Armored Division.

Sommaripa is buried at Luxembourg American Cemetery, Plot E, Row 15, Grave 68.

A very international team There are five different nationalities among the employees of the cemetery: Austrian, French, British, Portuguese and American. As for the visitors, according to the site’s guest registry, 57 different nationalities visited Luxembourg American Cemetery in July 2024 alone.

One of the employees worked as a gardener for approximately four years before becoming the administrative assistant. Her father also worked in another American Battle Monuments Commission site, Lorraine American Cemetery, for more than 30 years. Another employee has two family members buried in a World War I site, Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery, in France, Pvt. Salvatore Stagno and Pvt. Salvatore Zaffuto.

The turtles leave the site in the winter

Four fountains are present in the cemetery. Each radial mall contains two fountains overlooking three jet pools on descending levels. Bronze dolphins and turtles decorate the pools symbolizing resurrection and everlasting life.

To protect the turtle statues in the fountains from inclement weather and keep them in good condition, the cemetery workers unscrew them and store them during wintertime. They put them back in the fountains in the spring when conditions are better.

Luxembourg American Cemetery was established Dec. 29, 1944, by the 609th Quartermaster Company of the U.S. Third Army while Allied Forces were stemming the enemy's desperate Ardennes Offensive, one of the critical battles of World War II. The city of Luxembourg served as headquarters for Patton's U.S. Third Army. Sloping away from the terrace is the cemetery where the service members are buried or memorialized. Many of them lost their lives in the Battle of the Bulge and in the advance to the Rhine River.

For more than 100 years, the ABMC has been committed to its mission: honoring the service, achievements and sacrifices of the U.S. service members who made the ultimate sacrifice during American conflicts abroad, including World War II.

Sources:

Article created with Luxembourg American Cemetery’s team

ABMC Historical Services

ABMC documents, brochures and website.

ABMC Historical Files